How New Heights Community Health Centres and York Community Services minimized the culture risk when forming Unison Health and Community Services

Healthcare Quarterly Vol.16, No.1, 2013 p.85

By Jeff Chan

Abstract

Among the requirements for a successful merger or acquisition are strategic rationales, rigorous due diligence, the right price and revenue and cost synergies. However, bridging the culture gap between organizations is frequently overlooked. The leaders of new Heights Community Health Centres and York Community Services explicitly considered culture in their merger to form Unison Health and Community Services, and they used employee engagement surveys to assess culture in their merger planning and post-merger integration. How Unison Health leaders avoided the risk of culture rejection to achieve a successful merger, and the lessons learned from their experience, is the focus of this article. Patient Satisfaction: An Industry Focus, but What Have We Learned?

Much has been written about the failures of mergers, acquisitions and other forms of organizational and business combinations and, consequently, how to get things right, ensuring that

a merger creates value for shareholders or other stakeholders. Since most transactions attracting interest have occurred in the private sector, attention has focused on the financial aspects of success – revenue growth, cost reductions and shareholder value creation – and, as a result, on the financially driven causes of merger failures. Lost in the shuffle is the very real challenge posed by different or clashing corporate cultures – in particular, how to assess the relevant cultural differences and use them as a basis for pre-merger planning and post-merger integration.

Mergers and Acquisitions Fail More Often Than They Succeed

Achieving success in a merger or acquisition is difficult. Literature documenting a litany of dismal failures abounds. McKinsey & Company’s Scott Christofferson, Bob McNish and Diane Silas have pointed out a primary cause of these failures, observing: “The average acquirer materially overestimates the synergies a merger will yield. These synergies can come from economies of scale and scope, best practice, the sharing of capabilities and opportunities, and, often, the stimulating effect of the combination on the individual companies. However, it takes only a very small degree of error in estimating these values to cause an acquisition effort to stumble” (Christofferson et al. 2004: 1). The most common synergy value error according to Christofferson, McNish and Silas (2004) is in revenue increase projections. While top-line growth is the most common rationale for mergers and acquisitions, almost 70% of the mergers in their database failed to meet revenue expectations, and more than one quarter did not achieve even half of revenue synergy goals.

“Rather than blaming cultural differences for problems experienced during post deal integration, organizations should pre-empt these issues.”

KPMG tracks the performance of international merger and acquisition transactions in a biannual survey. While the principal reason for failure found by KPMG’s 2011 study mirrored that in the McKinsey study – overestimating the revenue synergies achievable – one other factor was notable. Survey respondents from 2008 to 2011 rated cultural differences as the third most- cited post-merger challenge. KPMG’s advice to companies is this: “Rather than blaming cultural differences for problems experienced during post deal integration, organizations should pre-empt these issues. By identifying and analyzing cultural variances upfront and addressing potential hot spots early on, companies can begin to forge a workable, if not fully common culture quickly, post-deal” (KPMG 2011: 12)

The Culture Gap

A high profile case, the Daimler-Benz–Chrysler merger, illustrates how culture can affect the fortunes of merger partners; this case was documented in 2002 in study by Professor Sydney Finkelstein of the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. In 1998, Daimler-Benz and Chrysler Corporation united to form DaimlerChrysler. Pre-merger, Chrysler was the highest-performing US auto company, with a focus on low- and medium-cost cars and trucks. But it only boasted a 2% market share in Europe and far less scale than Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Bob Eaton’s requirement.

Daimler-Benz, on the other hand, was primarily a high-cost luxury vehicle provider with only a 1% market share in the United States. The merger offered economies of scale and a partnership with a very profitable company (US$2.8 billion net income) with low design cost, an extensive US dealer network and a cash hoard of US$7.5 billion. On paper, this seemed the ideal corporate marriage.

The last thing on the minds of the executives at Daimler and Chrysler was that a corporate culture clash could derail the business benefits of the deal. Still, despite the solid strategic rationale, numerous and deeply felt cultural differences asserted themselves post-merger. Many dated back to the automakers’ historical competition and led to unco-operative behaviour and poor or no communication between management groups.

Because Daimler management opposed a fully integrated merger, the two organizations and senior management groups were never forced to come together. Nor was a new culture created to replace the two competing ones. This failure, along with the departure of key Chrysler executives, meant that cost, efficiency and revenue synergies never materialized and stronger competition (from Honda, Toyota, Ford and GM) eroded Chrysler’s market share.

The public sector, especially those bodies that operate in the troubled healthcare space, can learn a lesson from the experience of DaimlerChrysler.

Ontario’s Healthcare Environment

The Canadian healthcare landscape is under unprecedented pressure. While that is well recognized, the solutions are not always clear or universally supported. For example, as far back as 1996–2000, the Health Services Restructuring Commission in Ontario recommended the amalgamation of numerous hospitals province-wide and the restructuring of other health services. Benefits would have included not only cost savings but also better access, greater operational efficiency and improved quality of patient care.

Local Health System Integration Act and Other Regulatory Changes

In March 2006, the government of Ontario passed historic healthcare legislation. The Local Health System Integration Act changed the way Ontario’s healthcare system is managed by creating 14 local health integration networks (LHINs). These LHINs are required to enter into service accountability agreements with service providers including not only hospitals and long-term care facilities but also community health centres (CHCs) that are non-profit, community-driven and publicly accountable. The CHCs are funded primarily through accountability agreements with the LHINs. Members include clients, residents, community leaders, members of the business community and health and social service providers.

A Merger Is Born: The Unison Case

With more than 200 service providers, the Toronto Central LHIN looked to these providers to take the initiative. It is within this context that the New Heights Community Health Centres (NH) and York Community Services (YCS) contemplated merging in 2009–2010. Unison Health and Community Services was formally established on July 1, 2010. With more than 200 staff, Unison now serves over 12,000 clients from four main locations. Unison’s mission reflects its new integrated form: “Working together to deliver accessible and high quality health and community services that are integrated, respond to needs, build on strengths and inspire change.”

In 2008, the NH Board of Directors was undertaking a strategic planning process aimed at enhanced organizational effectiveness and efficiency. Early the following year, the NH board began work to realize its strategic priorities and enlisted the support of an external consultant to explore integration options. The board decided that a merger was the best option, based on the significant growth it needed to achieve back-office organizational efficiencies and to have a broader service and policy impact. Having reached this decision, the NH board determined that for both practical and strategic reasons, the preferred merger partner would need to be funded by, and located in, the same LHIN (Toronto Central).

In September 2009, NH approached YCS to begin discussions on possible integration activities, including a merger. One month after discussions began, both boards of directors agreed to investigate how well suited the organizations were to be merger partners.

A key decision made was to select the merged organization’s CEO prior to the merger approval to allay staff concerns at both organizations and ensure business continuity. That CEO was to be the executive director of NH, Andrea Cohen; Cohen became the standard bearer for the boards’ decisions and the key focal point for communications to both organizations on the merger plans and progress.

In April 2010, the two boards voted to approve the merger and form Unison Health and Community Services.

NH and YCS Cultures

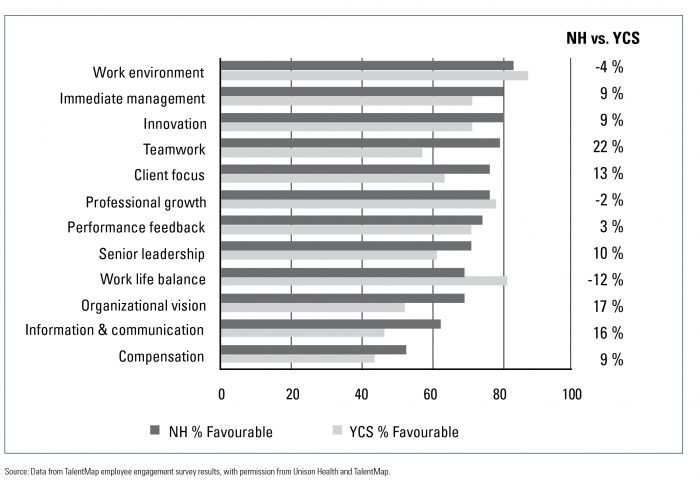

Early in the process, it was clear there were major cultural differences between the two organizations. Three sources of data were examined to gain a thorough understanding of culture differences. First were the results of two employee engagement surveys conducted at NH in November 2008 and YCS in March 2009. These surveys were designed and deployed by TalentMap, a consulting firm that designs and deploys employee surveys and provides consulting support to help client organizations in Canada and the United States improve employee engagement, organizational performance and business results. Second, a series of focus groups and anonymous surveys were conducted at both organizations. They were part of the due diligence process that examined how staff and management groups, and in York’s instance, the union, viewed the proposed merger. Finally, the two boards and management groups had made, and continued to make, anecdotal observations as the merger discussions progressed.

The three data sets underlined significant differences in the two workforces, in terms of their demographics (age, service and gender), their levels of engagement, how employees rated 12 engagement drivers and what managers and staff were excited and worried about with respect to the merger. Key cultural differences identified at NH and YCS were as follows (Figure 1):

- From the focus groups: Focus groups and anonymous surveys were conducted following the merger announcement to identify issues that both excited and worried staff and Commonalities existed but the distinct differences between the NH and YCS employees and managers allowed the merger team to focus on potential sources of resistance. With job loss a common concern at NH and YCS, the decision to limit any layoffs to management positions gained much staff support, although job loss remained, of course, an issue for managers.

- From board and management observations: Almost from the beginning, the NH Board was concerned about several aspects of the YCS organizational climate and For example, YCS was unionized, whereas NH was not. The culture at YCS had become very fragile – some would characterize it as battered – and professional turnover was high. YCS’s labour relations environment was contentious, with 25 unresolved grievances, two pending arbitration cases and a history of difficult contract negotiations. While the nature of the YCS culture was viewed as a high risk to the NH board, this became a positive factor in gaining the support of the YCS staff and managers who sought an improvement.

“Organization vision and senior management emerged as the top two drivers of engagement.”

Results

By October 2011, 18 months following the merger, in reviewing the following five measures, it was clear that the merger had been an unqualified success.

Financial Measures

The combined expenses for Unison were tracking to budget. The top priority goals of augmenting front-line clinical care and mental health and addiction services were met by reallocating cost savings from the elimination of duplicate back-office activities and jobs. Furthermore, the costs of the merger, including external consultants and severance payments, were offset by savings in previously planned but deferred satellite development initiatives.

Timetable

The merger was implemented on schedule, a rare occurrence. Merger discussions were initiated in September 2009, and by February2010, the organizations had reached an agreement to merge. By April 2010, both the LHIN and corporate member- ships had voted to approve the merger, and within the first 120 days, a new name and brand as well as mission, vision, values and operational plan for the new organization were developed.

It is from this date that the first year under the merger has been measured.

Service Metrics

Each of six performance indicators in the year ending March 31, 2011, improved over the pre-merger base, and met or exceeded the first year’s post-merger targets:

- Client service (number of clients/patients) per physician full- time equivalent at Keele-Rogers site (former YCS site): The three- year mean score pre-merger was The first-year goal was 1,000. The actual first year score was 1,682.2 or 68.2% better than the goal, and a 195% improvement over the pre-merger score.

- Service provision to clients through interdisciplinary care: Prior to the merger (2007–2010), 35% of client service was through interdisciplinary The first-year target was 40%, and the actual result was 43.66% – 9.1% better than the goal and a 24.7% improvement from the pre-merger score

- Number of patients receiving primary care service delivery at the Lawrence Heights and Keele-Rogers sites: The three-year mean number of patients receiving primary care service was 5,271. The goal of increasing this to 6,400 was met, with a total of 6,494 patients, an increase of 2%

- Capacity to provide primary care services for key clinicians at the Lawrence Heights and Keele-Rogers sites: The pre-merger (2009–2010) capacity score (a measure of vacancy rates reflecting the ability to recruit and retain physicians) was 08, and the goal was to increase this to 10.92. The actual first-year score was 11.76, 7.7% above the goal and a 93.4% increase from the pre-merger score.

- Registered patients with a mental health condition at the Lawrence Heights and Keele–Rogers sites: Prior to the merger, 673 patients with a mental health condition had been The first-year goal was to expand this offering and reach 700 patients. The actual number was 734, 4.9% above goal and a 9.1% increase.

- Overall client satisfaction at the former NH and YCS sites: The combined client satisfaction score at NH and YCS was 93%. The goal was to increase this already-high score to 95%, and the actual score for Unison was 96%.

Client Satisfaction

Seventy-one percent of respondents in the 2011 client satisfaction survey agreed that the merger had had an overall positive impact on programs and services. This was a good indication

that the changes affecting employees of Unison were mostly transparent to the patients, at a time when it would be expected that any changes in routine would adversely affect the satisfaction score.

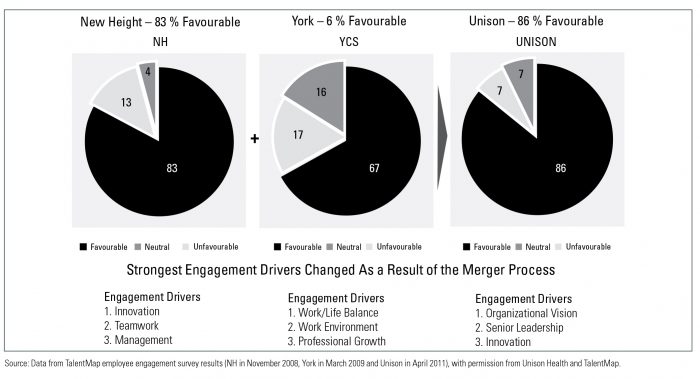

Employee Engagement

Overall employee engagement scores at Unison (86% favourable; Figure 2) exceeded the pre-merger scores at YCS (67%) and NH (83%), despite the expectation that the resulting engagement level would be a blend of the two organizations’ scores – a drop from the NH score and an increase in the YCS score. It was also anticipated that the engagement level would be negatively affected by the high amount of change in both former organizations. The fact that organization vision and senior management emerged as the top two drivers of engagement (see Figure 2) reflects the extra attention placed on defining and communicating the vision for the new organization, the appointment of the CEO both staff groups preferred and the retention of the NH executive team in key Unison roles. The Unison engagement score is 5% higher than TalentMap’s benchmark for 16 Ontario CHCs.

Although not an explicit goal of the merger, one consequence consistent with the high engagement score was that the workforces consisting of the unionized YCS staff and the non-unionized NH staff voted two thirds in favour of a union- free environment.

Lessons Learned and Key Messages

Although the Unison merger occurred within the Ontario healthcare environment, most of its lessons could apply to any organization:

- Despite frequently cited studies on failed mergers and acquisitions, mergers need not be The benefits of a strategically sound, well-executed merger can far outweigh the risks of a partially thought-out and poorly implemented one.

- The parties must fully understand and commit to the objectives and benefits of the

- Organizational culture needs to be considered in the due diligence process before a final decision to Employee engagement surveys can be used as a tool to assess culture, and identify merger barriers and the most effective implementation levers during the pre-merger and post-merger processes.

- Effective change management – especially related to stake- holder identification and communication – is essential.

Summary

Notwithstanding the reports of merger and acquisition failures

– those where the transaction failed to deliver expected results or, worse, destroyed value – there are now many prescriptions for improving the odds of success. The Unison merger team identified a new tool for overcoming one of the greatest impediments to the success of mergers and acquisitions, the organization culture divide. That tool was the application of the TalentMap employee engagement survey to assess cultural differences between organizations and to improve merger pre-planning and post-merger integration management. This should give confidence to leaders that they can achieve their goals and aspirations through a merger or acquisition without falling victim to one of the greatest risks, culture rejection.

“Despite frequently cited studies on failed mergers and acquisitions, mergers need not be feared.”

About the Author

Jeff Chan, BA, MBA, is principal of Growth Alchemy Group, in Markham, Ontario, and consults to organizations on corporate growth strategy and organizational performance. His interest in mergers and acquisitions comes from a corporate human resources career in which he has worked through acquisitions, mergers and joint ventures on both sides of the transaction, and from his career at McKinsey & Company, where he served a diverse client base in more than 30 countries on growth, corporate strategy and organization performance challenges that often used mergers and acquisitions as a key implementation lever. You can contact him by email at jeffchan@growthalchemy.com.

Comments are closed here.